As we approach the end of 2017, one might expect language and attitudes to be very different to those of the Middle Ages. And yet, there are some very prominent figures who seem to be stuck in the past.

Donald Trump, the US president, has once again dismissed his own infamous “grab them by the pussy” comments, one year after the 2005 Access Hollywood tape that revealed them came to light.

When his words first came to public attention, Trump then brushed them off as “locker room banter”, insisting that the public should focus instead on war and terrorism that were making the world “like medieval times”.

Numerous athletes came forward at the time to say that these are not the type of conversations that take place in their locker rooms. The debate continues to this day, with some supporting Trump’s comments, while women’s rights campaign groups refuse to let him brush it “under the rug”.

Though Trump tried to deflect attention onto historical horrors of war, this dispute has far more in common with medieval times than he might think. This very dispute mirrors the quarrel of the Roman de la Rose, which happened in the 15th Century – in which a female writer fought vehemently against depictions of sexual assault and “loose” women in entertainment.

Medieval attitudes

In medieval literature, women were commonly depicted as “easy”, particularly in the context of bawdy satire. Take, for example, Geoffrey Chaucer’s poems The Miller’s Tale and The Reeve’s Tale. In both of these texts women are depicted as enjoying, or easily recovering from sexual assault.

In The Miller’s Tale, when a clerk, Nicholas, decides he wants to have sex with his host’s wife Alison he grabs her “by the queynte [crotch]” and holds her hard “by the haunchebones [thighs]”. Although Alison initially tells Nicholas to get his hands off her, within three lines she has been won round and begins to conspire with her new lover against her husband.

In The Reeve’s Tale, two clerks take revenge upon a miller, who has duped them out of their money’s worth of flour, by raping his daughter and his wife. But by the end of the poem it is the miller who is battered and humiliated, while the women are not depicted as particularly bothered at being raped.

One of the most popular poems of the medieval period was Jean de Meun’s satirical, Le Roman de la Rose, which took a cynical view of the pursuit of love. In one scene a “jealous husband” gives an in-depth account of the vices of loose women: “Toutes estes, serés, ou futes, / De fait ou de volenté putes!” (All you women are, will be, and have been whores in deed or desire!). The poem was championed by many influential men of the period, and writers such as Chaucer drew upon it time and again in their own works.

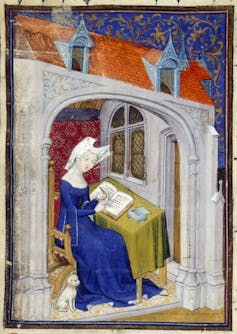

However, just as Trump’s comments have prompted protest today, back then it was down to Christine de Pizan – possibly the first European woman to make a living from writing, composing poetry and prose works in the late 1300s/early 1400s – to fight the patriarchy.

Fighting back

Born in Italy, De Pizan moved to France as a child when her father Thomas took up an appointment as the astrologer of King Charles V. De Pizan made use of the library available to her at the court, teaching herself to read and write in many languages. When she was suddenly widowed at the age of 24 she turned to writing as a way to make money to support her family. This was exceptional for a medieval woman, but the court paid her because they enjoyed her writing and the novelty of a woman’s works.

De Pizan’s writings were unique in providing a public voice for women at a time when they were not allowed to have one. She argued against the established tradition of women as “frail, unserious, and easily influenced” in medieval texts. She was a force to be reckoned with, and took particular objection to Le Roman de la Rose and its presentation of women.

In her campaign against the poem, De Pizan wrote letters to Jean de Montreuil (Provost of Lille) and Gontier Col (secretary to King Charles V), who publicly supported the poem. Detailing her concerns, she told them “I cannot remain silent”. They, however, dismissed her as a “femme passionée” – an emotional woman – who didn’t understand satire. De Pizan had a point, though. Even if words are not meant to be taken seriously, perpetuating negative stereotypes and normalising them as entertainment is harmful.

De Pizan did not remain silent. Her response was to compose literature that countered the male tradition, defending women and their place in society. In The Book of the City of Ladies, she wrote that she is “troubled and grieved” with men’s depictions of women as enjoying rape or not being bothered by rape even when they verbally object. And she makes further references to the visibility of domestic violence in her own neighbourhood.

In doing so, De Pizan brought to light the problem of trivialising abuse that was, and still is, prevalent in our society, and she encouraged early discussions of gender equality.

About Today's Contributor:

Natalie Hanna, Lecturer in English, University of Liverpool

This article was originally published on The Conversation.