For the past 20 years, an increasingly repetitive Hollywood has been serving up bland blockbusters with male protagonists supported by busty blondes on the narrative sidelines, pseudo-intellectual disaster sci-fi, and endless comedies about weddings or stag nights and being lost in Los Angeles. For high-profile culture, Hollywood has offered audiences an exceedingly narrow view of the world.

This may paint a picture of intellectual decay and creative stagnation, but it’s actually worse than that. For decades we have been subjected to films in which women are 10 or more years younger than their male counterparts; where a James Bond character is accepted as sexy and valued in his 50s and 60s, yet the female sidekick is seen as attractive only if she is under 30 and conventionally beautiful.

These women are flat, two-dimensional dolls devoid of darkness, moral or maternal imperfection, doubt or ambiguity. Their only function is to support men in their moral struggles and help them uncoil their fascinating internal complexities.

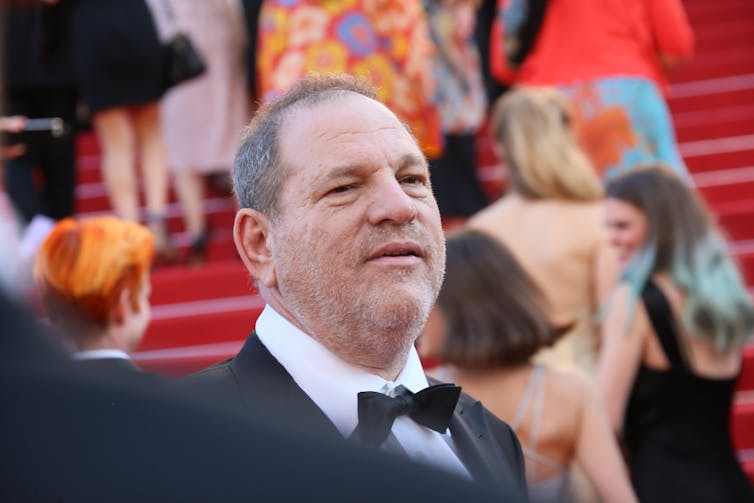

These narratives are not surprising given the demographics of decision-makers in Hollywood – that is male, pale and stale. The sorry Weinstein affair has particularly brought this imbalance of power to the fore. It turns out the accepted misogyny displayed in Hollywood film is a reflection of a misogynistic and abusive reality being played out in the dynamics of the film industry.

Power and glory

This concept of “narrative choice” is important. We know that people have a tendency to recreate their own vision of the world, not necessarily consciously or with malice. This is what they know and accept as the norm. But in choosing to recreate that narrative they are simply reinforcing and maintaining these norms.

In the context of Hollywood and Harvey Weinstein, the norms being reinforced and maintained are those of gender inequality. Hollywood men with power recreate their world of inequality on screen, promoting and legitimising tired and outdated stereotypes in our society and culture. It is these “norms” that allow an industry and the individuals within it to abuse and exploit, or to be abused and exploited without challenge or intervention.

In 2016, women made up just 7% of all directors of the top 250 films; in 2017 that went up four points to 11%. But Hollywood also suffers from a racial inclusion crisis, with very few ethnic minority producers and directors making it to the top.

In a multi-billion dollar industry there is a lot at stake in a very competitive and ruthless environment. As a result, narrative decisions in the biggest entertainment structure in the world are made by those in established positions of power – ruthless but risk-averse middle-aged white men. When this is translated into narratives about relationships and sexual power, dangerous precedents can be set.

For instance, Woody Allen’s films (such as Manhattan) contain numerous references to old men dating very young women, which in any other context would be considered concerning. Quentin Tarantino’s films overtly sexualise violence, often by trivialising the threat with humour.

Formulaic “chick flicks” such as Bridget Jones, reproduce the common movie assumption that a woman’s sole purpose in life is to find a man – and until she achieves that, she is a figure of fun or pity.

Equally predictable action films romanticise the extremes of masculine and feminine stereotypes – powerful men and submissive women. Most of them would not pass the so-called “Bechdel test” which asks simple but provocative questions: does a narrative contain two female characters, and do they speak to each other of something other than men?

Smashing the Hollywood monopoly

Luckily, on-demand television and media streaming arrived just in time to shake up, then directly challenge, the industry, saving it from itself. HBO, Netflix, Amazon and the BBC all began to offer narratives that went beyond the limited tastes and perspectives of the average Hollywood decision-maker.

Shows such as Luke Cage and Jessica Jones envisaged a superhero who is not white, or even a man. Orange is the New Black, I Love Dick and Fleabag depicted the never-seen before – multi-dimensional female characters exhibiting aggression, criminality, promiscuity, alternative sexuality and the capacity to shape and achieve their own ambitions.

Other complex, fleshed-out female characters could be found in Girls (a 21st-century Sex and the City), Glow (a comedy about female wrestling), Godless (a female Western series) and Top of the Lake (a troubled female detective drama).

And at last there was an array of morally ambiguous but rather sympathetic female characters: Peggy Blumquist in Fargo 2, Nikki Swango in Fargo 3, Scandi-Noir detectives Sara Lund (The Killing) and Saga Noren (The Bridge) and most of the female characters in Orange is the New Black.

Rather awkwardly and much too late, Hollywood has been trying to copy this trend. Now Star Wars has a female protagonist in the form of Rey. There’s even a female superhero in Wonder Woman – a protagonist proper, with no men attached to her story. Before them there were, of course, Ridley Scott’s female bad-asses such as Ripley in the Alien franchise, Thelma and Louise and Lieutenant Jordan O’Neil in GI Jane, who all fought for the right to be seen as human beings in a world otherwise run by men.

With the revulsion caused by the uncovering of Weinstein’s abuse of power and the exposure of unequal pay highlighting the shocking lack of gender equality, it feels like finally those narratives are about to change. Women everywhere celebrate every milestone on the road to equality – this year Greta Gerwig has been nominated for best director at the Oscars, and with only five other women ever nominated (and only one, Kathryn Bigelow, winning) in the awards’ 90-year history, this is a big deal.

About Today's Contributors:

Helena Bassil-Mozorow, Lecturer in Media and Journalism, Glasgow Caledonian University and Katy Proctor, Lecturer in Criminology and Policing, Glasgow Caledonian University

Logging you in...

Logging you in...