“Fortnite,” says explainer website Vox, “is kind of like Minecraft meets The Walking Dead – with a bonus Battle Royale attached.”Seven years in the making, Epic Games’ 2017 launch – a zombie survival game available across most console and mobile platforms – has captured the imaginations of players worldwide.

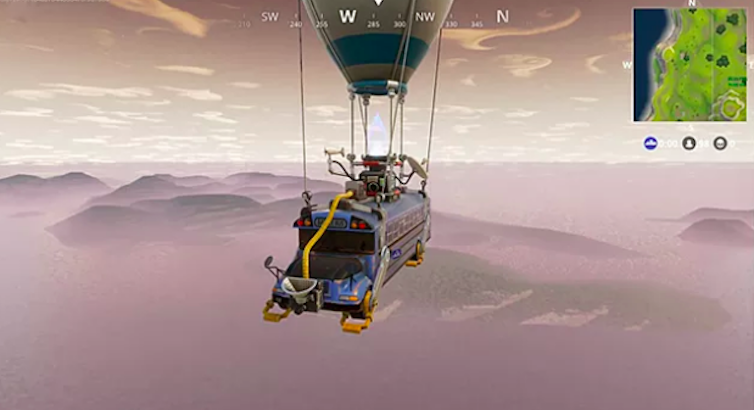

Fortnite is divided into two game types: Battle Royale, a free, online arena where 100 players compete to be the last player or team on the battlefield, and Save the World, an offline story-driven campaign that must be purchased. It is the former that has attracted the attention of players and fans, with the number of online communities growing by the day.

A wide range of design decisions could be attributed to Fortnite’s success, but I’d like to focus on understanding the play experiences that entice players to keep on playing. By examining Fortnite through game analysis tool the Mechanics, Dynamics and Aesthetics (MDA) Framework – an academically developed means to assess the design of experiences in games – we can identify the experiences on offer to players.

Fortnite offers something different for a whole range of players and the way they like to play games. This is what is known as the “aesthetics” of the game, which explains the emotional responses that players have as a result of play. These principles help to move the conversation from the abstract “games are fun” type of assessment to more concrete judgements about player experiences. In the context of Fortnite, using the MDA Framework, five aesthetics are at play which help to define its success: sensation, narrative, challenge, fellowship and pastime.

High five

Sensation concerns the sense of pleasure derived from an experience that offers something unfamiliar to players. But Fortnite shares its range of “mechanics” – actions available to the player – with many other games. Shooting big guns, for example, is a common point-and-click experience popularised in many games, such as Doom and Quake.

Massive multiplayer online games have been around for decades, with World of Warcraft the best known. Fortnite’s building system, which allows players to construct forts and defensive walls, is not dissimilar to that in Minecraft. PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG), Fortnite’s closest competitor within the Battle Royale genre, has had success in its own right with multiple awards.

So if Fortnite is not the first game to offer these characteristics, how does it stand out as a superlative gaming experience? It can be argued that this comes from the game’s feel: handling the survival hysteria of the game while forgiving players’ lack of precision in shooting; providing security for master-crafters who have taken time to master the art of building; allowing breathing space to form strategies; and creating a cartoon style that reminds players to enjoy the post-apocalyptic environment. This could only be achieved with rigorous testing during development.

Play sessions of Fortnite embody narrative – each game session has its own unique, player-centric story. One player holding down a fort with their teammates using an assorted arsenal of weapons is different to that of the sole wanderer gathering wood to build a sky bridge. Yet both types of players may feel similar levels of enjoyment and satisfaction in their accomplishments. This sense of satisfaction is what encourages players to play again and create new narratives.

The challenge, or set of obstacles to overcome, has little to do with Fortnite’s environment. A threatening atmosphere and difficult-to-master building techniques provide the only difficulties from the game’s perspective. The real challenge is the player’s understanding and use of available space and resources and their level of skill. There is a steady learning curve to each player action – movement, shooting, building, resource management – and their relationship to each other within a tense play session.

Mastery of such a system requires extensive time and effort, but these higher levels of competence are rewarded with social stature within the game, such as costumes and body armour that suggest a certain level of skill and experience.

There is no denying that Fortnite features some form of fellowship, a community of active participants. Game modes such as “Duo” and “Squad” allow players to team up with their friends or other players online. A hierarchy of skill recognises the “best-of-the-rest” as they rise to the top of the leaderboards. Curated videos and livestreams connect people with a shared interest in the game. This community presence has undoubtedly played a massive role in ensuring Fortnite’s recent success, and will continue to define the game’s meteoric trajectory so long as it is kept hydrated with stimulation.

Finally, Fortnite reinforces the mantra of games as a pastime – people are willing to put time and concentrated effort into playing it. This can also be determined by their consumption of wider networks related to the game itself, such as videos and livestreams, blogs and forums.

Free no-risk fun

We also cannot forget the free-to-play nature of Fortnite’s Battle Royale mode in encouraging players to adopt and stay. Beyond investing their time, there is little commercial risk for players when choosing to play the game. This has worked with other games, too – the limited-time free-to-play approach was instrumental in the success of soccer video game Rocket League.

Like all games, Fortnite will have its life cycle and then eventually retire to the annals of gaming folklore. Players and online personalities will continue to gun down zombies, fight over supply drops and construct pillars of vantage until someone becomes the very last last-player-standing.

About Today's Contributor:

Andrew James Reid, Research Associate, Glasgow Caledonian University

This article was originally published on The Conversation.