The collector dreams his way not only into a distant or bygone world but also into a better one.Seeking exile from the growing anti-Semitism in his native Germany, author Walter Benjamin’s words are just as relevant today as they were when he wrote them in the early 1930s. Living in Paris, Benjamin loved rifling through what he saw as capitalism’s ruins in the fusty and out-dated 19th-century arcades, delighting in the mass-produced detritus that he found in secondhand shops. Freed from what he described as the “drudgery” of being useful, Benjamin’s objects were transformed by the act of collecting and acquired a quasi-magical status.

-Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project.

To place collective memory under scrutiny is not easy and hence the significance of Albert’s new survey exhibition, Visible, at Brisbane’s Queensland Art Gallery. It was the conspicuous absence of Indigenous representation in visual culture that initially drew Albert as a child to secondhand shops in the 1980s.

By making the invisible visible, Albert stages a direct confrontation with Australia’s difficult and racist not-so-distant past. Akin to Benjamin’s quirky assortments of stamps and snow domes, new meanings are acquired through Albert’s reassembling of disparate objects into a collection. What comes to the fore in the show is how deftly he traverses mediums, moving from his iconic text-based assemblages of the 2000s to photography, installation and newly commissioned sculptural work.

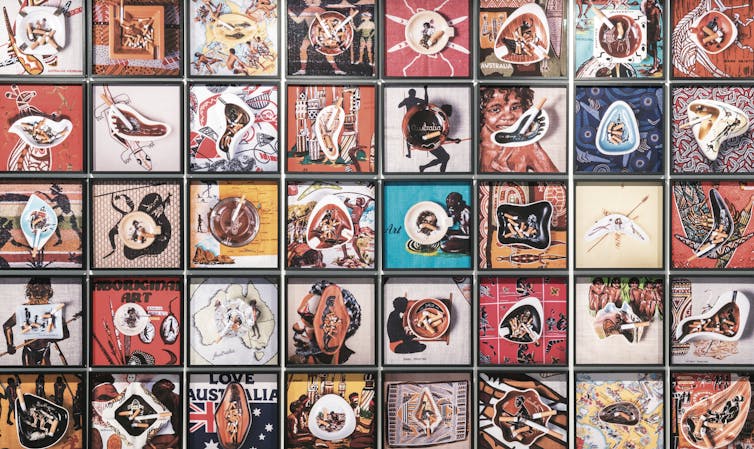

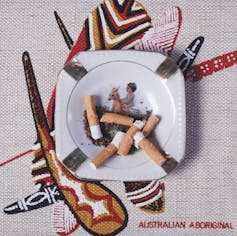

Mid Century Modern is a 2016 series continuing Albert’s reactivation of kitsch memorabilia. He has carefully arranged a series of ashtrays in a grid-like formation. His trademark sense of humour and playfulness is on display here. His point, however, is deadly serious: what does it mean to stub a cigarette out on a black face? It is this tension between the absurd and serious, visible and invisible that prevents his work from slipping into a predictable monotony.

Collaboration is a core theme that runs through Albert’s practice. Consider, for example Moving Targets 2015, the result of a collaboration with Stephen Page, the Artistic Director of Bangarra Dance Theatre. Taking its departure point from a 2012 police shooting of two Aboriginal teenagers in Sydney’s King’s Cross, the multimedia installation is comprised of a stripped out, dilapidated car. Inside the car are screens and the viewer is invited to contemplate the final moments of the boys’ joyride as Bangarra’s Beau Dean Riley Smith dances with increasing agitation and intensity.

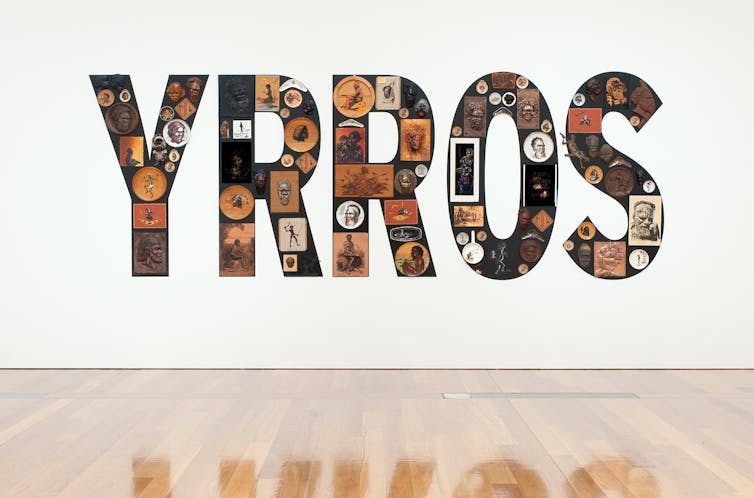

Albert has since requested that Sorry be reversed to instead spell YRROS, effectively parodying and evacuating the sincerity of the Apology. Words and meaning exist as a series of conventions. In this act of reversal, Albert underscores how arbitrary and fragile these conventions are. Ten years have now elapsed and with discussions pertaining to Indigenous constitutional recognition reaching a political impasse, we are left to uneasily consider: what, if anything, has changed?

⏩ Visible is at Brisbane’s Queensland Art Gallery until 7 October.

About Today's Contributor:

Chari Larsson, Lecturer of art history, Griffith University

This article was originally published on The Conversation.