|

| A British passport on a British flag (image via Shutterstock) |

Mirela left Croatia in 1991 because of the civil war in Yugoslavia. Her husband Frank grew up in the Republic of Ireland. Both are worried Brexit has left a deep scar through British society, one that it will take years to heal. They also worry about the impact of Brexit on their mixed-nationality families and how to mitigate it.

“It is a smart option to get as many passports as you can,” Mirela, who holds a passport from the newest EU member state, Croatia, told our team. For Frank, an Irish national, his Republic of Ireland passport is the best to have under current circumstances due to the additional arrangements between the Republic of Ireland and the UK regarding the status of their citizens.

Mirela, who has seen how quickly a country can implode and how rapidly the value of a passport can change, is not persuaded. “Things can change quickly,” She says.

These comments are a snapshot of the many, often animated and tense, conversations EU families have had since June 2016.

Boris Johnson, the British prime minister, recently said the chances of a Brexit deal are now “touch and go”, having previously said the odds of a no-deal Brexit were “a million to one”. This has reopened the debate around the protections provided by the “EU settled status” arrangement, further igniting EU citizens’ anxieties and moving more people towards applying for a British passport via naturalisation.

The latest Home Office immigration statistics released in August show that since March 2019, when the scheme was officially launched after a pilot phase, more than a million EU nationals have applied for “EU settled status” which allows them to continue living in the UK after Brexit.

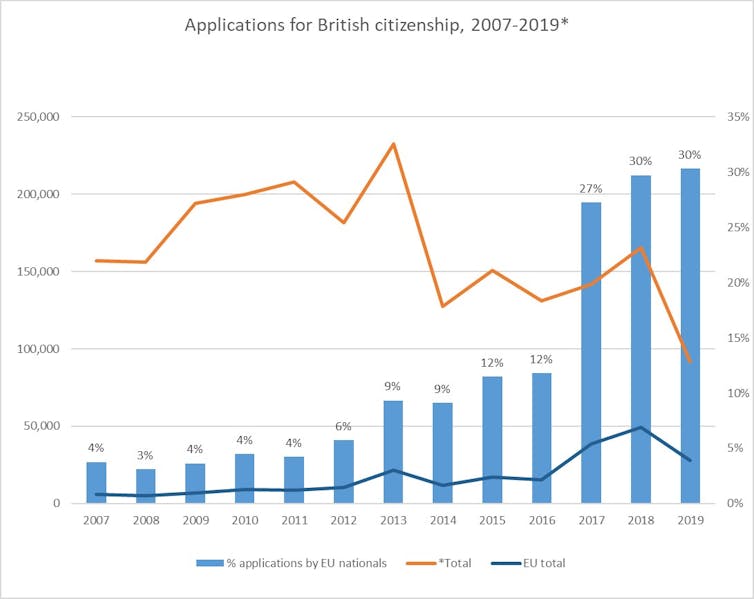

Data also reveal that the share of British citizenship applications by EU nationals has increased from 4% in 2007 to 30% in June 2019. At the time of the 2016 EU referendum, applications by EU citizens accounted for 12% of the total.

|

| Applications for British citizenship, 2007-2019. Source: Home Office, Immigration Statistics (Citizenship tables), August 2019. Data for 2019 cover Q1 and Q2. Elaboration: Eurochildren |

Our study – EU families and Eurochildren in Brexiting Britain – shows that for some EU citizens, the result of the EU referendum has meant a sudden and even shocking realisation of the fragility of their legal position in the UK. Others, instead, had already encountered the UK government’s “hostile environment” and experienced being at the receiving end of the virulent anti-immigration rhetoric of some British newspapers.

Indeed, research shows that Polish and other Central and Eastern EU nationals in the UK have felt negatively targeted by British populist media since much before the June 2016 EU referendum. This might explain why, similarly to Romanian citizens, they began to apply in sizeable numbers for British citizenship even before the referendum and are currently the two main countries of origin of citizenship applicants, followed by Italians, Germans and French.

Given the above, it’s unsurprising, therefore, that while the increase in applications for British citizenship from citizens of so-called “old member states” (EU14) (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Republic of Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden) has been steeper since June 2016, the increase among citizens of “new member states” – divided into EU8 (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia) and EU2 (Romania, Bulgaria), according to their date of accession to the EU – began earlier.

In 2013, 47% of all British citizenship applications by EU citizens came from EU8 nationals, 27% from EU2 nationals, and 25% from EU14 nationals. By contrast, in 2019, EU14 citizens accounted for 51% of all EU applications, with the EU8 accounting for 30%, and the EU2 18%.

Newspaper reports often take this as evidence of EU nationals racing to secure their status in the UK. But there are an estimated 3.7m EU nationals in the UK, and only one third has so far applied for settled status and 130,000 for citizenship since the EU referendum.

Our findings have highlighted how some EU citizens, particularly children, risk falling through the cracks of the settled status registration process and, as a consequence, may encounter insurmountable obstacles to later accessing citizenship.

A hard decision

There are a range of economic, social and legal considerations, including fees, eligibility restrictions, and the right to dual nationality that may preclude EU nationals from applying for citizenship. We also found that for those in the position to do it, it is rarely a decision that is taken lightly. Many going through the process feel like the decision has been forced upon them by circumstances, and ultimately decided to apply with family and the future of their children at the forefront of their minds.

Family composition, in terms of the countries of birth of both parents and children, also plays a role in the decision-making process. We found that in mixed nationality families, including those with a UK-born partner, leaving the UK and “going home” is a rarely a realistic option and that naturalisation becomes the only viable way of keeping the family safe and together.

We also found that attitudes towards naturalisation vary significantly among EU nationals. Better off and more educated EU nationals, for example, are more reluctant to apply to become British, on ideological and political grounds. Among EU14 nationals this response to naturalisation was more frequent.

Others, like Mirela, take a more pragmatic approach to acquiring a British passport, particularly those who have previously experienced the constraints and difficulties of visa restrictions and come from countries with lower trust in state institutions and the rule of law (for example, Romania and Bulgaria).

The outcome of the EU referendum is tearing some EU families apart, uprooting children and parents, spreading them across borders, and forcing families to reconsider their future in the UK. Under these circumstances, becoming a British citizen is often a defensive move – for those who can afford the £1,349 per person application fee – and a way for them to “take back control” over their lives after years of uncertainty.

About Today's Contributor:

Nando Sigona, Professor of International Migration and Forced Displacement and Deputy Director of the Institute for Research into Superdiversity, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.