Sweden and New Zealand are aiming for 2045, Finland for 2035 and Norway for 2030 – the most ambitious of any government. Extinction Rebellion has called for the UK to eliminate all carbon emissions by 2025. Our recent working paper explores the justification for these various targets.

The starting point is the global carbon budget calculated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). This is the total amount of carbon that can be emitted into the atmosphere from now until the end of this century. The most recent estimate of a global budget that would offer a 66% chance of limiting climate warming to within 1.5C above the pre-industrial average is 420 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide.

Working from here to a carbon budget for each country is both a technical and an ethical question. Using the UK as a detailed example, a simple proportional allocation would give the UK a budget of approximately 2.9 billion tonnes. But given the UK’s historical responsibility for carbon in the atmosphere and the undeniable need for development in the poorest countries in the world, there is a very strong argument that the UK should adopt a fair carbon budget somewhat lower than this. So, for example, if the poorer countries in the world were to have an allowable carbon budget just one-third higher than the richer countries, this would lead to a fair carbon budget for the UK of around 2.5 billion tonnes.

The question of how long this budget might last has no simple answer, because it depends how fast carbon emissions are cut over time. Remaining within any given budget depends inherently on the emissions pathway the country follows. If we cut emissions faster, we can afford a later target. If we cut too slowly, the budget will be exhausted, and we would be faced with the task of installing uncertain and costly negative emissions technologies to take carbon out of the atmosphere for the rest of the century.

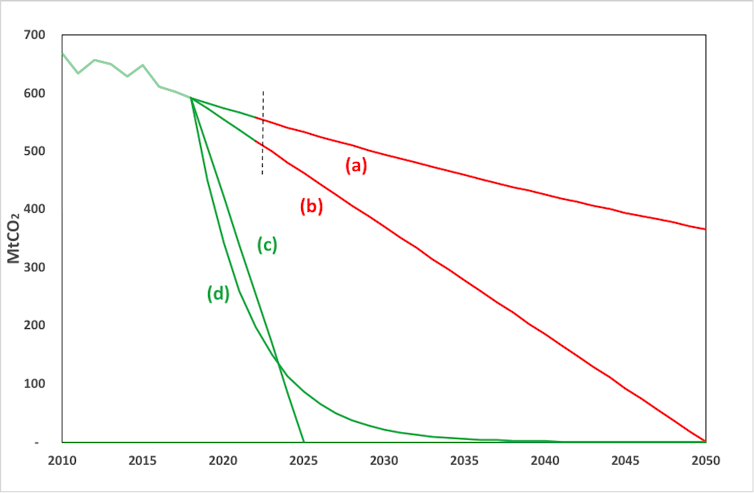

The UK’s carbon footprint in 2018 was about 590m tonnes, measured on a “consumption basis”, which includes the carbon in imports but excludes that of exports. This footprint has been falling slowly (at around 1.5% a year) since 2010. But if it continued to fall this slowly, the carbon budget would be exhausted by 2023, in just four years’ time (Scenario a).

Even if we assume a straight-line reduction to zero emissions in 2050 (Scenario b), we would still generate a carbon overdraft approximately three times our allowable budget. In fact, the latest date by which we could draw a straight line from our current level of emissions to zero and still remain within the budget would be 2025 (Scenario c).

What is notable about this pathway is that, within little more than a decade, carbon emissions must already have fallen to a very low level. With a 24% annual rate of reduction, UK emissions in 2030 would only be 22m tonnes – less than 5% of the current level of emissions. Only a small programme of negative emissions technologies would be needed to achieve net zero at this point.

Clearly the challenge is still colossal. A 24% reduction in emissions amounts to a cut of 140 million tonnes in the very first year alone. The UK has never achieved anything close to this since its carbon footprint was first measured in 1990. In 2009, when the economy was in recession, the carbon footprint fell by 80m tonnes, while its best post-crisis reduction saw a fall of only 38m tonnes in 2016.

It is dangerously misleading for advanced nations to set target dates as far out as 2050. Doing so ignores the importance of staying within a fair carbon budget and gives a false impression that action can be delayed. In reality, the only way to ensure that any developed country remains within its fair budget is to aim for an early net zero target. For the UK, that means bringing forward the government’s target by at least two decades.

This might all seem daunting, but every year that progress is delayed, the challenge only gets bigger. Remaining within a fair carbon budget for the rest of this century requires deep and early decarbonisation. Anything else will risk a climate catastrophe.

About Today's Contributor:

Tim Jackson, Professor of Sustainable Development and Director of the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity (CUSP), University of Surrey

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.