|

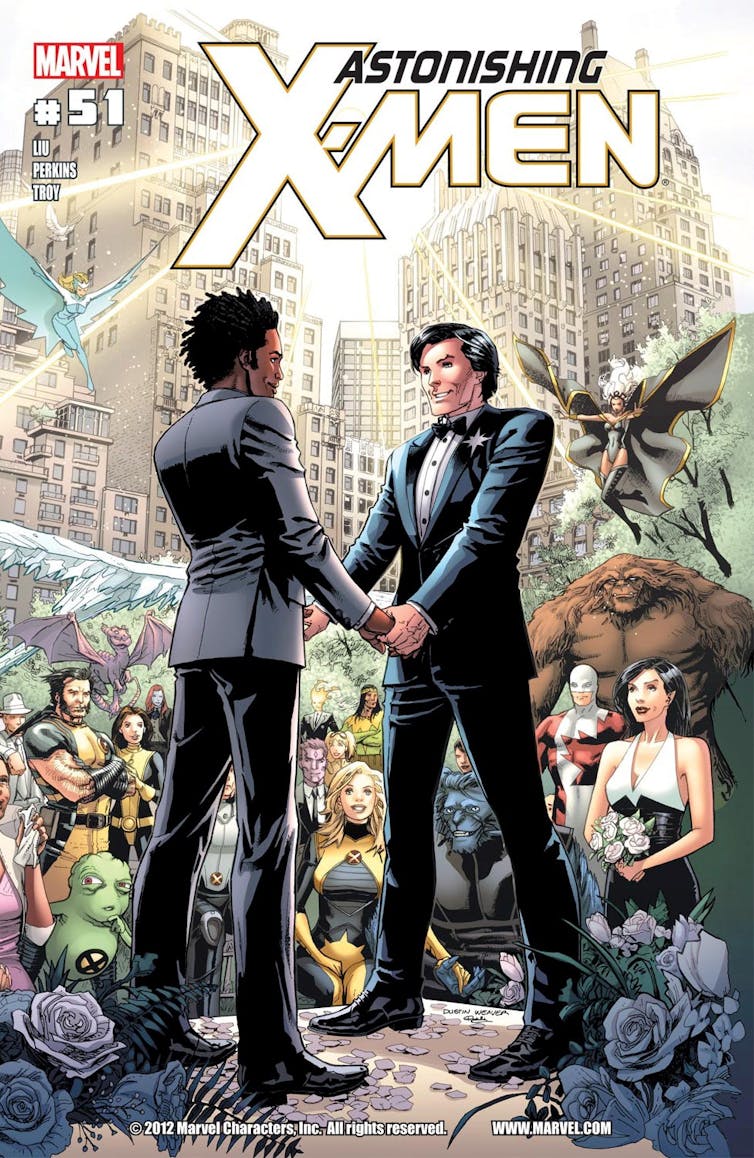

| Northstar’s marriage was prominently displayed on the cover of ‘Astonishing X-Men #51.’ (Marvel) |

There’s a reason for that.

The 1954 Comics Code Authority — a censorship bureau that policed comics content — explicitly banned “sex perversion or any inference to same,” which comics scholar Hilary Chute notes is “a clear reference to homosexuality.” The Marvel Universe as we know it began in 1961, with the launch of Fantastic Four #1. Thus, Marvel Comics was, from the outset, actually prohibited from depicting gay characters.

So how do you a write a queer character at a time when comics are expressly forbidden from featuring queer characters?

In a word: delicately.

The slow coming out

It wasn’t until 1992 — three years after a major revision to the Comics Code officially opened the door to depictions of LGBTQ+ characters — that Marvel had their first openly gay superhero. In Alpha Flight #106 written by Scott Lobdel, the character Northstar (alias Olympic ski champion Jean-Paul Beaubier) declared: “I am gay.”Even then this move was met with outrage by Marvel’s corporate leadership, Marvel Comics historian Sean Howe explained in his book Marvel Comics: The Untold Story.

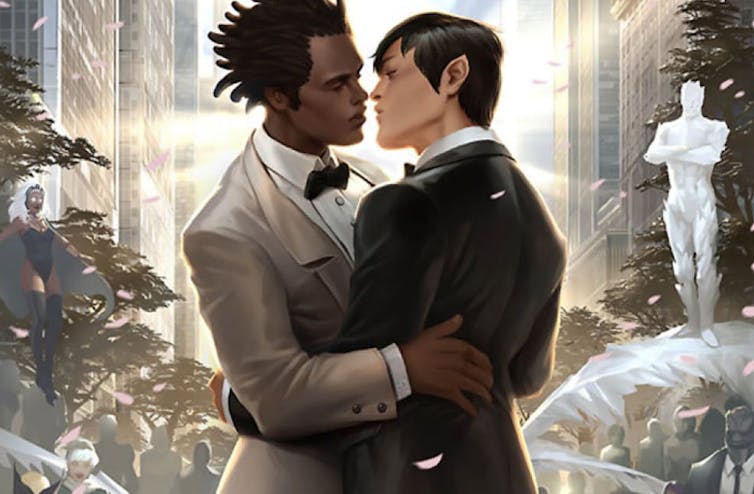

Twenty years later, Northstar would also feature in Marvel’s first same-sex marriage, an event that was prominently depicted on the cover of Astonishing X-Men #51.

|

| Astonishing X-Men #51. Written by Margaret Liu and illustrated by Dustin Weaver, published June 20, 2012. (Marvel) |

A hotbed for queer subtext

At the time, X-Men comics were already a hotbed for queer subtext. Comics scholar Ramzi Fawaz notes that Claremont’s X-Men “articulated mutation to the radical critiques of identity promulgated by the cultures of women’s and gay liberation.”

Another comics scholar, Scott Bukatman, puts it more simply and says: “mutant bodies are explicitly analogized to … gay bodies” in Claremont’s X-Men. It is no surprise then, that Marvel’s first gay superhero should emerge from this series.

|

| Marvel’s first gay superhero emerged from the X-Men series. (Marvel) |

Byrne described the impetus of Northstar’s sexuality:

“There needs to be gays in comics because there are gays in real life. No other reason …. The population of the fictional world should represent the real world. That’s why I created Northstar — I felt the Marvel Universe needed a gay superhero (even if I would never be allowed to say it in so many words in the comics themselves), and I felt that I should create one, rather than retrofitting an existing character.”

Validation through storytelling

Northstar’s sexuality first surfaces in Alpha Flight #7 (1983) when he meets up with “an old friend” named Raymonde who is strongly hinted to be a former lover. In the story, written by Byrne, Raymonde comments on Northstar’s good looks. He also references the secretive nature of his relationship with Jean-Paul: “Then you have not really told your sister all about me, after all, Jean-Paul? I thought that would have been odd.” |

| From Alpha Flight #7 (Marvel) |

When Raymonde is later murdered, Northstar snaps with blind rage. The narrative caption tells us: “And Raymonde had led him out of that dark fear, into the bright clear light of self-acceptance.”

In 1983, the narrative of a former lover being murdered and thus spurring the superhero to action and emotional eruption was already a comics cliché. But staging that through a same-sex couple establishes a sort of subtextual validation of Northstar’s relationship as something more than the Comics Code Authority “sex perversion” label.

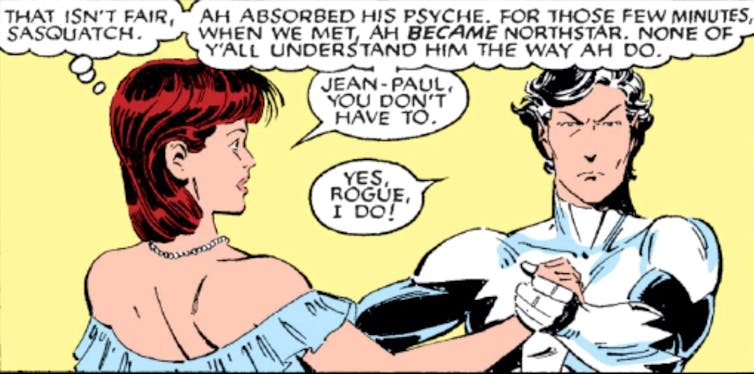

Two years later, in the 1985 limited series X-Men and Alpha Flight, Northstar’s sexuality is once again woven into a key story, this time written by Claremont. After having his consciousness briefly absorbed by the X-Man Rogue, Northstar becomes furious that she now knows his “secrets.”

In a misguided attempt to help Northstar, Rogue then asks him to dance at a very public reception. When Northstar’s own teammates make fun of the incongruity of Northstar dancing at a ball with a woman, Rogue thinks “None of y’all understand him the way ah do.”

In the face of this ridicule, a stoic Jean-Paul takes Rogue up on the dance. She remarks “You don’t have to,” to which he replies, “Yes, Rogue. I do.”

|

| From X-Men and Alpha Flight #1 (Marvel) |

Northstar

It’s a sympathetic portrayal of the character that helps to normalize the concept of a gay superhero, even if Marvel couldn’t identify him that way at the time.

Whether through delicate subtext or comics covering wedding events, Northstar holds a uniquely prominent and, at times, poignant position in the history of LGBTQ+ superheroes.

As we come to understand the importance of diverse representation within the superhero genre, this is a character that needs to be known, discussed and hopefully appreciated.

About Today's Contributor:

J. Andrew Deman, Professor, University of Waterloo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.